FALL OF ELLEN GRACE

Cut off in early bloom

Nipped by Death's certain hand

Borne on a seraphs golden wings

To that far distant land

Lost is our darling Grace!

No! Lost is not the word

She found in Heaven above

A dwelling with the Lord.

Let us prepare the way

To meet our pearl on high

And join her once again

In mansions of the sky

These words appeared in the North Eastern Ensign, a local paper from Benalla in Victoria, on Friday 4 April 1890. They were chosen by Thomas and Jane Lloyd for their ten-year-old daughter, Ellen Grace Lloyd – who met a tragic end a few months earlier while walking home from school.

It was the 22nd of January 1890 – just another day in the small farming community of Lurg, four miles South of Benalla. Farmers were working in their fields, a local farmer Thomas Lloyd had milked the cows before making the journey into Benalla for business and his young daughter Ellen Grace Lloyd was walking the few miles from the family home to the Lurg State School with her younger brother John.

Back at the Lloyd farm – George Lionel Lambert was beginning his day. He was employed as a general labourer by the Lloyd family. Twelve months earlier Lambert, an Englishman, showed up at the farm asking if there was any work for him. Thomas Lloyd took him on and he had worked steadily for the family for the past year. It seems Lambert had had as much as he could handle of the labouring life, having a week earlier approached a solicitor in Benalla to ask what the best way was of sending a considerable amount of money from England to Australia as he wished to purchase his own farm in the Benalla district and settle down.

The day unfolded without incident, and when school was dismissed Ellen and John began to make their way back to the family farm. At the same time, George Lambert had finished his work for the day and had had asked Jane Lloyd if there was anything more for him to do. Jane said she had no further work for him – so George said he fancied doing some reading but did not currently have a book so he was off to Edward Henry’s place to borrow one. George walked towards the Henry’s farm, which was in the direction of the local school.

Ellen and John were making their way through the paddocks from the school back to the family farm – a shortcut they took every day on a well-worn track, keeping off the main road. It was about five o’clock in the afternoon, and being January there would have been sufficient light for the children to walk home in. John was trailing behind, but he could still see his sister walking ahead of him.

George Lambert, making his way from the farm, had reached a wooded section of land where the Greta-Lurg Road meets the Upper Lurg Road. And this I where he waited.

As Ellen approached the wooded area, Lambert struck – chasing the young girl into the bushes.

Trailing behind - John Lloyd could see his sister being chased by Lambert into the scrub – and as he ran closer to see what was going on he saw his older sister running once more, this time with her torso covered in blood. There is a bit of a discrepancy between the official record and what was reported in the newspapers as to what John did next. The Argus Newspaper reported that John was too frightened to see what was to follow when Lambert dragged Ellen off the track into the bushes, and states that he ran home to fetch his mother. But – at the inquest, John James Lloyd, just shy of eight years, testified that he found his sister, lying on the ground with her throat cut. Ellen looked up at John – but did not, and most likely, could not say anything. From the fence line, John then saw George Lionel Lambert walking toward him, blood streaming down his chest. Before Lambert could reach John and his sister, he collapsed on the ground.

I suspect The Argus didn’t want to report that an eight-year-old boy found his sister in such a state for the sake of decency, or maybe the story just got a bit muddled between Benalla and Melbourne – either way, I’m sticking with the official record.

So – back to the story. John ran home to sound the alarm – running ¾ of a mile up the track to tell his mother what had happened. Jane Lloyd and her eldest son rushed back to the bushes at the intersection and found Ellen as John had described, lying dead on the ground with her throat cut, a very deep wound having been inflicted.

Lambert’s body was found in the same state by the police when they arrived – with Constable Duncan McLennan stating “He had his boots, coat and trousers on and they were saturated in blood with the front of his trousers opened but no exposure”. The constable seems to have been making a point to mention that Lambert did not appear to have exposed himself to, or sexually assaulted Ellen. McLennan searched the body and found a knife, a number of keys and an empty razor case on Lambert. He also had on him his birth certificate, a rough last will and testament, a photo of him and an unknown child taken in Melbourne and a few other documents – more on those below.

Constable McLennan moved the body to the Lloyd residence and awaited the arrival of his colleagues from Wangaratta, Patrick Blade and Arthur Steele. For those with an interest in the Kelly Gang, and given that is Lurg smack bang in the middle of Kelly Country the name Arthur Steele would be familiar. He was the man credited with capturing Ned Kelly and firing the shot that brought him down at the Siege of Glenrowan ten years earlier. Steele played a very small part in this story, assisting with the search of the bushland where the attack took place with Constable Blade.

The search of the bushland took place in the early hours of the morning after the shocking murder-suicide. Margaret Lloyd, sister of Ellen appears to have been at the scene of the crime at some stage, as she testified at the inquest that she found a razor handle, which she handed to Sergeant Steele. The only other item of note found at the scene, other than signs of a struggle and a great deal of blood, was a small bottle of violet ink found by Constable Blade.

An inquest was held at the Lloyds residence the same day – with testimony heard from a number of people regarding the movements of Ellen and Lambert the previous day. Thomas Sydney Davies, a doctor – examined the bodies of both Ellen and Lambert – determining that events had unfolded as one would have guessed – a tragic murder-suicide committed by George Lionel Lambert. He had used his newly sharpened razor and cut twice into the throat of Ellen Grace Lloyd, the second cut severing the carotid artery causing death in a few moments. On examining Lambert’s body, he concluded that Lambert’s single cut to his own throat was as indeed self-inflicted and that “he had evidently began tentatively”.

Now we know what happened – but we don’t know why.

A common thing in 19th-century inquests, you get the facts relating to the cause of death, and not much else. Sometimes a witness might make some additional and otherwise interesting comments in their testimony but in general, once the cause of death is determined and the facts are there to support it, proceedings stop.

While not specifically referred to in the inquest proceedings the documents found on Lambert were submitted as exhibits and survive to this day. The details in those documents reveal his motives, but, the best place to start Lambert’s story is back at the beginning, in Dorset, Dorchester in England.

George Lionel Lambert was the third son of Francis Henry Lambert and was a member of an old a well-respected family in the area, living in the centre of town in a house named none other than ‘Lambert House’. Tragedy struck the family when Lambert was only young, with he and his six siblings becoming orphaned. George had an older brother, John, and two younger brothers William and Arthur who went to Australia and George who was described as a “wild a reckless youth” was sent to school at Weymouth by his guardians. Proving too reckless for this school he was soon dismissed – and he met a similar fate at other schools he attended afterward. At one of the schools it was reported that the master found a pistol under his pillow and when questioned about the presence of such a dangerous weapon on school grounds Lambert swiftly jumped out the window and ran off. He was found walking the streets almost naked sometime after.

At some point in time his guardians determined that a stint in the mercantile navy might straighten the wayward teenager out, but, as the Bridport News printed in 1890 “his behaviour at sea was so bad that he was dismissed after the first voyage”. If the mercantile marines couldn’t sort Lambert out, his guardians thought perhaps the navy could. Despite one newspaper report stating that “in a short time he was dismissed from her Majesty’s service for bad conduct or deserted his ship”, his official navy record, retrieved from the British National Archives, states that his character was “very good” while serving aboard two different training vessels, the Impregnable and the Boscawen, between June 1881 and May 1882 when presumably due to some illness or injury he was invalided to the military hospital at Haslar, at Gosport.

Relying on only one article written on the other side of the world does pose some issues for me. For starters, this article, the only one that provides some insight into the previous George Lambert’s life before arriving in Australia did state that Ellen Grace Lloyd was the niece of Ned Kelly, which is certainly not the case. So it does cast some doubt over other statements in the article – another being that upon arriving in Australia Lambert was leading a “depraved and dissipated life of which this tragedy is undoubtedly the sequel” and that those who knew him when he was a boy described him as a “heartless young scapegrace”. A scapegrace, I’ve since learned, is “a mischievous or wayward person, especially a young person or child” in other words, a rascal.

One last note on the article – you can imagine that the English papers would hardly be trying to defend the man given the gruesome crime he committed (and I’m certainly not attempting to either), so it is safe to say the article was always going to be along the lines of a troubled boy from way back.

At some point after May 1882 Lambert came to Australia – possibly as early as 1883 when a notice appears in The Age newspaper from a George Lambert to a John James Lambert (same name as George’s brother, living in Melbourne at the time) stating the following:

“If you still hold my father's will, the property holds good” – cryptic, but perhaps referring to the family property back in Dorset or some other item or items belonging to their father that George may have been in possession of?

This is the last trace of George Lionel Lambert until the tragic events in January of 1890.

Now, to the documents found on Lambert.

Exhibit I

Lambert's birth certificate, which he had sent away for in September, writing to a man named John Sparks and asking him to obtain a copy from London for him. Sparks appears to have known Lambert, in a short note written with a copy of the certificate he says “I hope you are now doing fairly well, believe me”.

Exhibit II

The next document was written by Lambert over a month before Ellen’s murder, it reads as follows:

“I give and bequeath unto Thomas Lloyd everything I possess on conditions that he bury me”

“God in his infinite mercy has decreed me to act thus. Great God is our father, and unto Him, we go, my darling Ellen Grace and I. We shall have no more earthly troubles and trials. God have mercy on our souls. God be merciful unto us sinners. God has called us to himself. We shall both meet in heaven. It is God’s will then we both go together”.

The document was signed by both Lambert and Ellen, but at the inquest, Ellen’s sister Mary stated that Ellen’s signature was not written in her hand – and declared it a forgery by Lambert.

Exhibit IV contained a short note:

“Thomas Lloyd to get my letters from the general post office and have the money contained therein to bury me according to the right of the Catholic Church”.

From the short notes that Lambert had penned in the weeks leading up to the events of January 22nd, it’s evident that he had an obsession with young Ellen, and perhaps knowing that he could never be with the young girl or act on any impulsion he made have had towards the girl – he arrived at the conclusion that the only way the two could ever be together was in death.

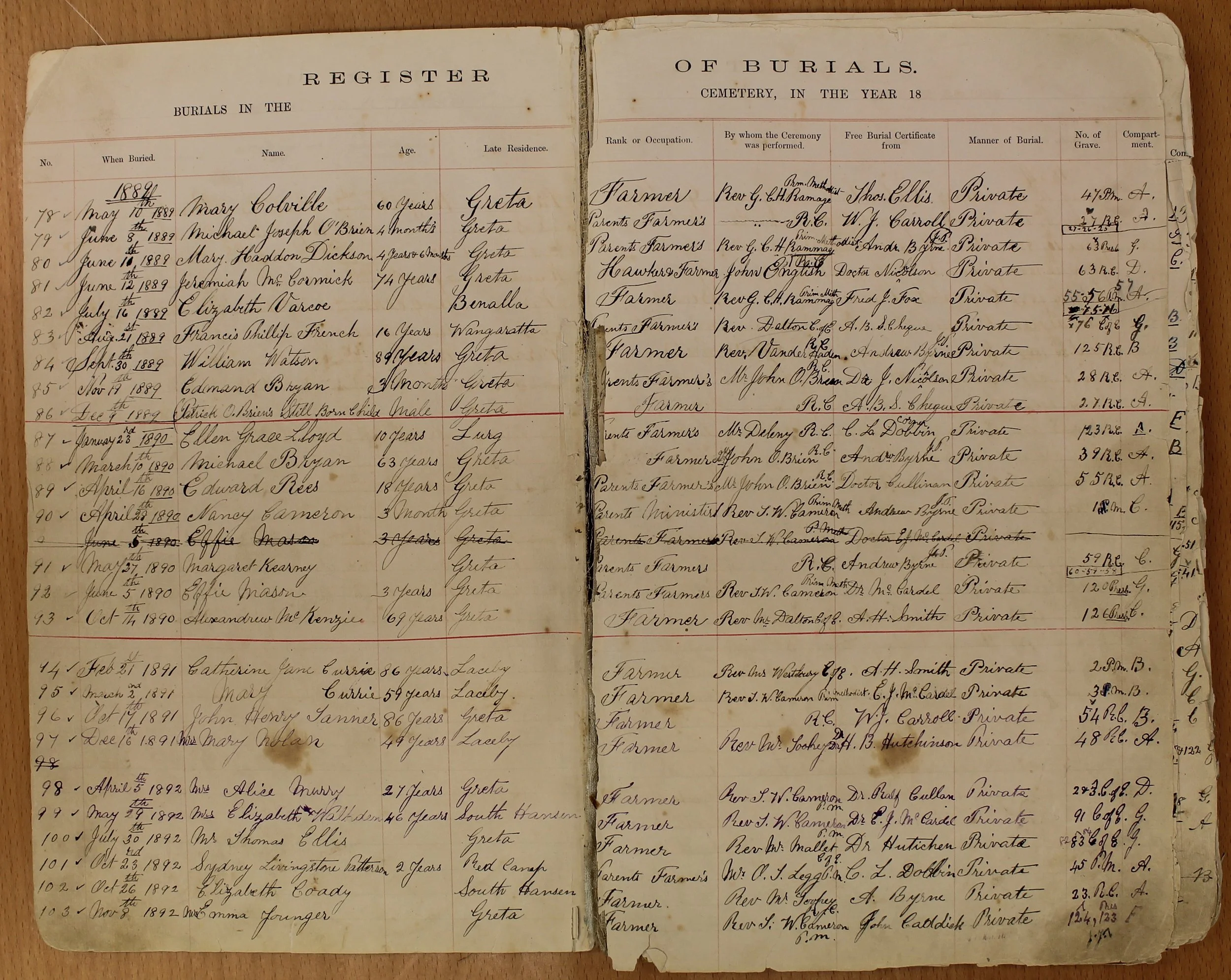

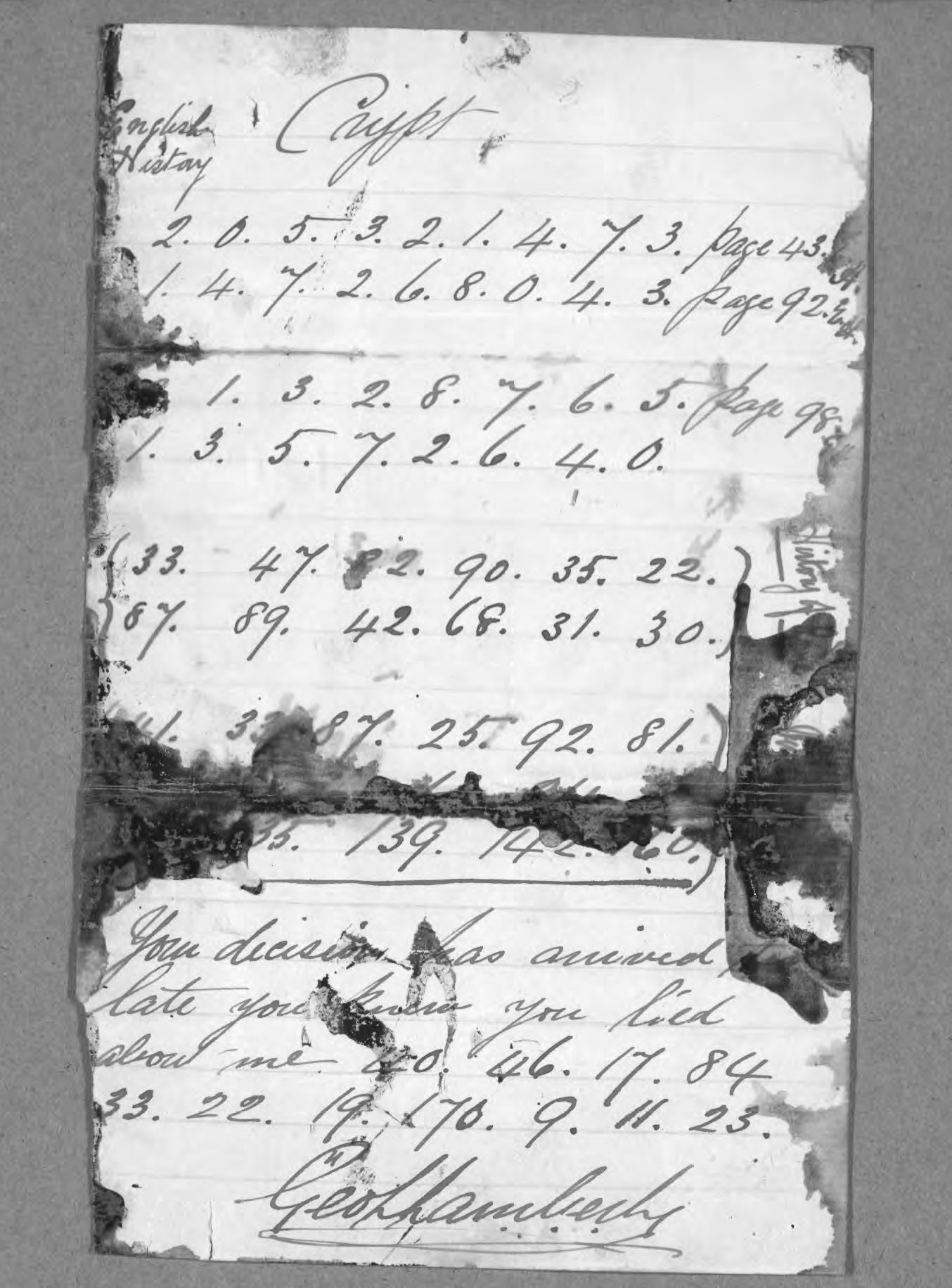

Exhibit V The most intriguing piece of the puzzle was the response that Lambert had begun to draft to John Sparks – containing a series of codes and ciphers containing a hidden message.

The cryptic message contains what appears to be two types of ciphers – a book cipher, where a series of numbers are provided with a page refer3ence and a specific book mentioned. Though, Lambert's codes were not specific enough to be useful in cracking his cipher over a century later – the two texts are “English History” and “History of Rome”. If these codes were something real and not something made up by Lambert, then the references must have meant something to John Sparks. The other form of cipher appears to be a substitution cipher – a string of random letters that when substituted for other letters would reveal a message.

Lambert's message went as follows:

J Sparks

{Book code, English history} concerning {substitution code} everything to T.L, presumable Thomas Lloyd. More book codes and finally “your decision has arrived too late, you know you lied about me”

George Lambert

When Lambert’s birth certificate was forwarded to him by John Sparks, the letter shows that Sparks was writing from Crewkerne, Somerset. He was a solicitor, in his 60s, with over 40 years of experience practicing law, but I can find no link between Sparks and Lambert. Was there some deeper relationship between them – something so clandestine that would see them is secret codes? Was he the old family lawyer, or was that unlikely given the distance between Dorset and Crewkerne? Were the codes just a figment of Lambert's imagination and when received by Sparks would be met with a lot of confusion.

As Lambert had killed himself after murdering Ellen Grace, it seems no further investigation was made regarding his connections back home or the meaning behind the codes – but it seems this mystery will endure.

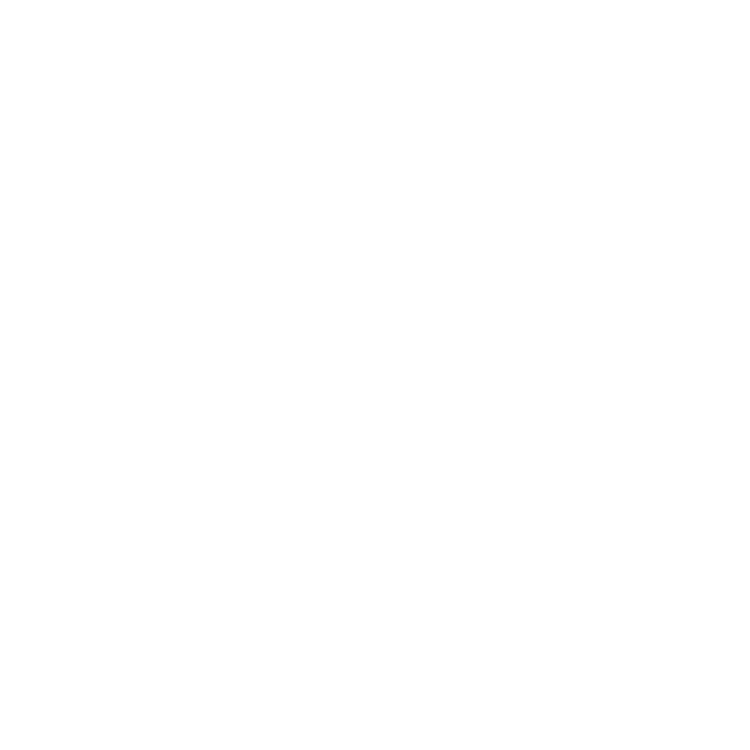

Ellen was laid to rest on the 23 January 1890 at Greta, while the same day a Lambert was unceremoniously buried at Benalla.

Greta Cemetery burial register, shoawing Ellen race Lloyd's entry

Lambert's birth certificate, 1865 birthplace Dorchester

A portion of Lambert's codes - undecipherable.

George Lionel Lambert, with unknown child. A Photo included in the qinuest file.

Another example of Lambert's code - its meaning remains a mystery